April 23, 2014

Solar/Storage Threatens Utility Model, Says Morgan Stanley

By Todd Olinsky-Paul

We here at Clean Energy Group have been touting the growing market for solar combined with electricity storage for a while now. But apparently when Morgan Stanley says something, people listen.

The multinational financial services corporation set off a minor furor in the investment world when it published a neat bit of research titled “Clean Tech, Utilities & Autos; Batteries + Distributed Gen. May Be a Negative for Utilities.” The main conclusion of the report – “utility customers may be positioned to eliminate their use of the power grid” – sparked a flurry of discussion about the “disruptive technology” that is the marriage of PV and battery storage.

What’s new about this is the recent announcement by Tesla that it plans to build a $5 billion “gigawatt scale” battery manufacturing plant somewhere in the southwestern U.S., a plant that the company projects will produce more lithium-ion batteries than the entire global supply for 2013, while halving per-unit costs. Already, SolarCity and Tesla have teamed up to offer a solar/storage package to residential and commercial customers. The specter of plentiful, inexpensive batteries, coupled with the continuing decline in PV costs and projected increases in fixed grid charges related to non-generation-related utility costs, was enough to convince Morgan Stanley that many utility customers could find it cheaper to supply their own power as early as 2018.

For example, based on the assumptions that California utility bills will increase 5% per year, solar penetration will reach 20%, and solar customers will pay just half the fixed grid fees paid by typical utility customers, Morgan Stanley projects that an average residential utility customer in California would be paying $.26/kWh for electricity in 2020. But, says Morgan Stanley, by 2020 Californians should be able to go completely off-grid with a solar/storage system for 10 to 12 cents per kilowatt hour. And the off-grid solution has the added benefit that when the grid goes down, your home or business won’t.

Currently, most people who install solar panels retain their grid interconnection; even those with batteries tend to view the grid as a desirable backup system. But Morgan Stanley sees a potential problem with this approach; as more and more people self-generate, the cost of utility infrastructure is spread over a smaller and smaller rate base. That means the remaining customers on the grid will see increases in their electric bills.

The utilities have been arguing this point to state regulators, which is why a number of states are now considering allowing a fee on self-generation. But Morgan Stanley sees a pitfall in this strategy. The biggest danger for utilities, the report argues, is that they will push regulators to raise fixed grid charges past a tipping point, driving more and more customers to disconnect entirely. “The higher the fixed grid charge required of distributed generation customers,” Morgan Stanley says, “the more likely they are to buy batteries and go off the grid.” If Tesla were to provide an emergency backup service to their solar/storage customers – say, emergency battery replacement in case of equipment failure – Morgan Stanley sees the possibility that solar/storage users could unplug from the grid permanently. To avoid this, Morgan Stanley believes utilities should integrate distributed generators into their business model, viewing them as an asset rather than a threat.

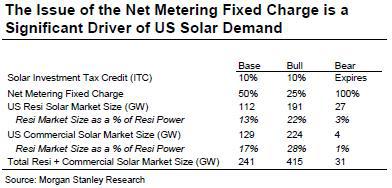

The fixed grid charge is one of two main drivers Morgan Stanley identifies as likely to impact the growth of the U.S. solar market. The other is the 30% federal solar investment tax credit (ITC), which has provided significant financial support for the deployment of distributed PV. The sensitivity of the market to these two drivers is illustrated in the following table, which shows Morgan Stanley’s projected results for three scenarios involving changes to fixed grid charges and the ITC.

What Morgan Stanley does not factor into its projections is the value of the resiliency benefit that solar/storage technologies can provide, perhaps because so far, nobody has come up with a way to calculate this. But it’s clear that resiliency does have value. Think of it as a form of insurance: if the grid went down, and your home or business lost power, what would the damages add up to? And what would you be willing to pay to ensure that wouldn’t happen? Big finance and tech firms, such as Apple, Microsoft, Goldman Sachs, Verizon and AT&T, have already invested in resilient power, because their business losses would be enormous without it. As the cost of solar and batteries continues to fall, more and more companies and individuals will make the same calculation. And, as is already happening in the Northeast, more and more states will turn to resilient power technologies to keep critical facilities up and running during natural disasters and their associated grid outages.

Storms are becoming more frequent and more severe; utility power costs are rising; and resilient power technologies, such as solar/storage, are becoming better and cheaper. More and more, these “disruptive technologies” are looking attractive. If utilities get Morgan Stanley’s message, and become more willing to work with distributed generation and resilient power rather than fighting it, so much the better.